A couple years ago, I don’t remember how many, one of you asked if I would preach on the texts and stories that aren’t chosen by the lectionaries, so that we aren’t cycling through the same set every three or four years, but would get a broader view of scripture.

I think this is a good idea – but it’s a bumpy ride, because the texts and stories not chosen are often not chosen for a reason – they are difficult or complicated to listen to and think through, and, to be honest, most congregations don’t want to try. People generally come to church to be inspired, to leave feeling good, with a vague sense of familiarity with what is being preached, and don’t come expecting to leave with difficult questions hanging in the air. Cain and Abel, for example, don’t appear in any preaching cycle. Theirs is not a particularly edifying tale… but still it is important and an interesting story on many levels. I think Genesis is a book to read and to work through – and, especially in light of what’s happening in the Middle East between Palestinians and Jews this week, these stories are amazingly pertinent. So, these are the reasons I’m picking my way slowly through instead of hitting the high points and best loved episodes. My perspective on Genesis is that the early chapters are attempting to tell us about the nature and will of God and the nature and ways of people… and to point out the gulf that separates these natures.

The key, I believe, is to read Genesis through the lens of, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and soul and strength and mind, and you shall love your neighbor as yourself.” That should be the banner heading each week. I believe that is the heart and essence of God’s will for us. It was to be the guiding principle of the ancient Israelites and it is what Jesus taught and lived 2000 years later. I think these early, mythic stories are told to explain our behavior and our difficulties with living this ethic, of upholding this minimum standard of life before God.

Last week we pulled a thread of Abraham’s saga to follow Sarah’s part in the covenant and the promise of Isaac. The thread tugs at two other stories. After Isaac’s birth, Sarah decides that Ishmael (Abraham’s son with her handmaid/slave) is competition for her own son’s inheritance. She tells Abraham to send Hagar and Ishmael out of the camp, out into the desert to wander and die. Abraham is loth to do this because it is his first-born son, but God tells him it will be okay, and in fact, God hears Ishmael’s cries and provides for them, repeating the promise to Hagar that Ishmael will become the father of a mighty nation. That storyline ends in this way: 21:20 “God was with the boy, and he grew up; he lived in the wilderness, and became an expert with the bow. 21He lived in the wilderness of Paran; and his mother got a wife for him from the land of Egypt.” Ishmael and Isaac reunite a few chapters later to bury their father. Judaism credits Abraham through Ishmael to be the father of the Arab people, and Abraham through Isaac to be the father of the Jews. After Hagar and Ishmael leave, we are told that Abraham, his family and itinerant herder household continue to prosper as resident aliens in the land of the Philistines. There is a seemingly random interlude at the end of chapter 21 describing a peaceful co-existence covenant that Abraham forms with King Abimelech and the establishment of the well of Beer-sheba.

And then, when Isaac’s storyline picks up again, we wish that it hadn’t.

Genesis 22

After these things God tested Abraham. He said to him, ‘Abraham!’ And he said, ‘Here I am.’ 2He said, ‘Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt-offering on one of the mountains that I shall show you.’ 3So Abraham rose early in the morning, saddled his donkey, and took two of his young men with him, and his son Isaac; he cut the wood for the burnt-offering, and set out and went to the place in the distance that God had shown him. 4On the third day Abraham looked up and saw the place far away. 5Then Abraham said to his young men, ‘Stay here with the donkey; the boy and I will go over there; we will worship, and then we will come back to you.’ 6Abraham took the wood of the burnt-offering and laid it on his son Isaac, and he himself carried the fire and the knife. So the two of them walked on together. 7Isaac said to his father Abraham, ‘Father!’ And he said, ‘Here I am, my son.’ He said, ‘The fire and the wood are here, but where is the lamb for a burnt-offering?’ 8Abraham said, ‘God himself will provide the lamb for a burnt-offering, my son.’ So the two of them walked on together.

9 When they came to the place that God had shown him, Abraham built an altar there and laid the wood in order. He bound his son Isaac, and laid him on the altar, on top of the wood. 10Then Abraham reached out his hand and took the knife to slay his son.

11But the angel of the Lord called to him from heaven, and said, ‘Abraham, Abraham!’ And he said, ‘Here I am.’ 12He said, ‘Do not lay your hand on the boy or do anything to him; for now I know that you fear God, since you have not withheld your son, your only son, from me.’ 13And Abraham looked up and saw a ram, caught in a thicket by its horns. Abraham went and took the ram and offered it up as a burnt-offering instead of his son. 14So Abraham called that place ‘The Lord will provide’; as it is said to this day, ‘On the mount of the Lord it shall be provided.’

15 The angel of the Lord called to Abraham a second time from heaven, 16and said, ‘By myself I have sworn, says the Lord: Because you have done this, and have not withheld your son, your only son, 17I will indeed bless you, and I will make your offspring as numerous as the stars of heaven and as the sand that is on the seashore. And your offspring shall possess the gate of their enemies, 18and by your offspring shall all the nations of the earth gain blessing for themselves, because you have obeyed my voice.’ 19So Abraham returned to his young men, and they rose and went together to Beer-sheba; and Abraham lived at Beer-sheba.

The word of the Lord……. Thanks be to God

Sarah was wrong, of course.

So was Cain.

They assumed love is a zero-sum game. God chose Abel’s offering. Ishmael was Abraham’s firstborn son. Therefore, Cain and Sarah reasoned, in order for the second to ‘win’ the father’s affection and recognition, the first must be removed from the equation. Love can’t possibly encompass both equally, favoring this one’s art or that one’s scope while cherishing both together.

I think we would say that God’s love can easily, readily, willingly, whole-heartedly, eagerly cherish not only both, but all. But that fear, that kind of self-doubting envy of the other runs deep. It’s the scarcity model – always fearing there won’t be enough for us if someone else gets plenty. We understand the logic of Cain and Sarah even as we cringe at their actions. And we don’t believe that God acts in that way, being the God of creation and love. We believe God is loving and good. And so we are shocked by scriptures like today’s.

“Abraham.” “Here I am, Lord.” “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt-offering on one of the mountains that I shall show you.”

Where did this come from? The cherished, promised son through whom, according to God’s word, Abraham and Sarah create nations and kings, this son is to be killed?

God’s logic is illogical.

And God’s request is ungodly.

The neighboring religious cults practiced human and child sacrifice, we are told, but the God of Israel, the one God, the God of life, always condemned it. Punished it. And Abraham, who came back time and again to argue and bargain for the lives of those in Sodom didn’t speak a word of protest? “3So Abraham rose early in the morning, saddled his donkey, and took two of his young men with him, and his son Isaac; he cut the wood for the burnt-offering, and set out and went to the place in the distance that God had shown him.”

We don’t know which of these aspects of the story is worse.

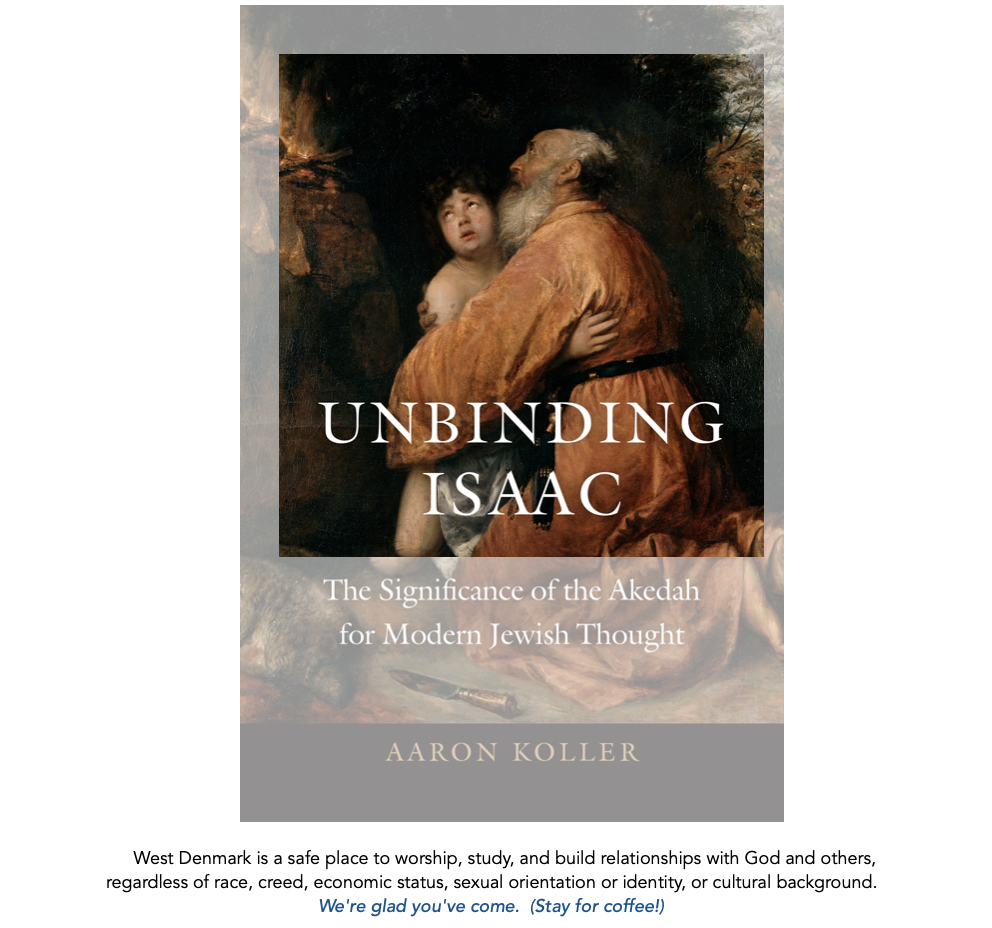

Jewish rabbis and scholars since Medieval times onward have left behind written explanations and ponderings about this, too, of course. I try to read Jewish commentaries as well as Christian thought. The Akedah, as this passage is called, meaning “the binding,” became in Jewish thought the supreme example of self-sacrifice in obedience to God’s will and the symbol of Jewish martyrdom. Both Abraham and Isaac were bound. Abraham is hemmed in behind and before. How does one find a way forward when the choice is between love of God and love of your own God-given child?

Christian Bible headings call this story the sacrifice of Isaac. Christian commentaries (not surprisingly) jump to Christ – there are so many similarities in the language and imagery to God’s beloved, innocent son, who carried his own wooden cross to the place of death, three day’s journey through the wilderness, the sacrificial lamb God would provide, like a ram caught in the thickets, discovered as a substitute for our death. It’s all there in this ancient story. And it’s fine and beautiful in prefiguring the Christian faith – except that in this reading and others in the Old Testament, God rebukes human sacrifice, staying the hand of Abraham.

In Hebrew it’s called the binding, and that is helpful, because there are four characters who are bound. Isaac, of course is tied with the cords of death. We don’t hear much from him on this journey, other than his wondering about the lamb for the sacrifice as he carries the wood on the way up the mountain. The lamb, Abraham assures him, God will provide.

Abraham, too, is bound. He has followed the guiding hand of God for decades believing in the promise of heirs and descendants. Finally, at a very old age, when his wife Sarah was beyond the way women, they are given this beloved son whose name means delight and laughter. And God, who has promised progeny as numerous as the stars, as plenteous as the sands of the shore, now says offer this only child of promise as a sacrifice. We are told it is a test, Abraham is not told that. For Abraham to disobey the command of God is wrong, and to obey this command of God is wrong. Abraham is stuck between the love of a father for his son and the love of God with whom he has a history and who asks – who demands – to be trusted. It is a terrible, fraught, binding place to be.

Sarah is not part of the story. She is not mentioned either biblically nor rabbinically. However, we have affinity for Sarah. She is bound by silence, by gender, by the cloak of invisibility. She is an unseen, unrecognized victim of this word of God. In Sarah, we find a person to embody our agent-less suffering, our inability to understand, the taken-for-grantedness of those occupying the background of life… Sarah is us, in our human condition, bound by the indeterminacy, the necessary incompleteness of God’s plan, the effect of decisions and actions that fan out beyond the predictable, expected conclusions.

But God, too, is bound.

God is bound to our limited understandings, our misunderstandings of God’s will and way, our misunderstandings of God’s voice.

As it stands, this story is a polemic against the sacrifice of human lives for the mistaken understanding of God’s will. God’s love overrides God’s law. “For I desire steadfast love and not sacrifice, the knowledge of God rather than burnt offerings.” God says through Hosea. “A broken and contrite heart, a humble spirit are acceptable offerings,” the psalmist says for God.

In the 1967 Six-Day War, when for the first time the generation of founders were too old to fight, and their children fought in their place, the akedah remained a powerful symbol. In a post-war collection of interviews, The Seventh Day: Soldiers Talk About the Six-Day War (Hebrew: Siaḥ Lohamim, 1967; English, 1970) a father is recorded who said: “We do knowingly bring our boys up to volunteer for combat units…. These are moments when a man is given a greater insight into Isaac’s sacrifice. Kierkegaard asked what Abraham did that night. What did he think about? … He had a whole night to think…. It’s a question that touches on the very meaning of human existence. The Bible says nothing about it… For us, that night lasted six days” (p. 202).

The weariness and pain of the akedah come to the front after the Yom Kippur war. The poet Menahem Heyd writes: “And there was no ram – /and Isaac in the thicket.// And the angel did not say lay not/ and we – / our son, our only son, Isaac.” (“Yiẓhak Halakh le-Har Moriah” (“Isaac Went to Mount Moriah”), Yedi’oth Aharonot, December 28, 1973.)

The pain is particularly intense because no ram came to replace Isaac.

This current version of the war between Israel and Palestine is a war of extremists willing to sacrifice their sons and daughters, their souls for a cause. It is political, not religious, not godly, not a holy war. There is no one to stay the hand of slaughter. There is no ram caught in the thicket. Palestinians are not Hamas, they are people forced from their land and homes by Israeli settlers and walls. And Jewish people are not the state of Israel to be sacrificed for political means or exterminated. They are people. We watch the news with horror and fear for where this war will run over and spill out of the small container of Gaza and Israel and the West Bank. We pray for a ram to be spotted in the thicket, some new alternative, some faithfulness to the God of love and recompense… some hope.

Abraham’s test still speaks. “Are my human creations capable of trust,” wonders God. “Are they capable of listening for my voice, of discerning the way of life in the midst of Chaos and death?”

Abraham’s test speaks to the binding of our lives — choices we have to make when it seems no right choice can be made, or those times when we are carried along, swept up within a powerful force without choice, or when our voice isn’t heard, times when we seem to occupy the acted upon background.

How do we hear God’s word when it contradicts our will? Do we listen beyond our fear, or follow, or trust, or open our minds to the possibility of a ram stuck in the thicket behind us? How do we unbind Isaac? Do we have the nerve to answer, “Here I am. Speak, Lord, and I will listen?” Jesus complained of those who have eyes but do not see, ears but do not hear. The life of faith is not one to undertake without our whole hearts and intellect and strength. It demands no less than the best, most flexible, adaptable, creative spirit we have to offer.

In the early rabbinic period, the Akedah found it way into the people’s public prayers of intercession and it stands for you: “May the God who answered Abraham our father on Mount Moriah answer you – hearken to the voice of your crying this day, and loose the cords of your binding.”

Peace be yours this day.